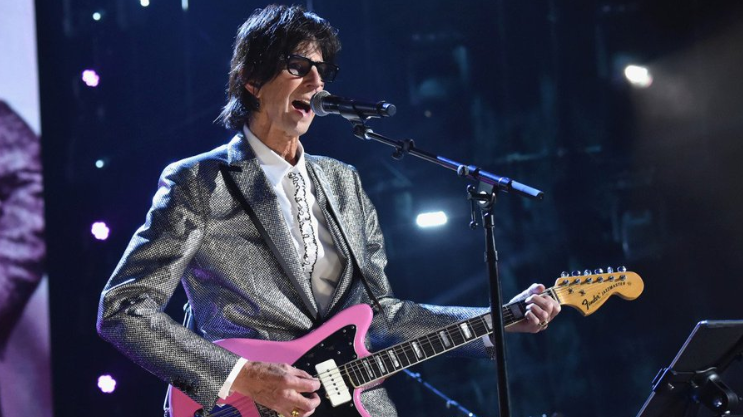

RIP

Ric Ocasek of The Cars found dead in New York City apartment, he was 75

Rolling Stone — Ric Ocasek, the idiosyncratic singer and guitarist for the Cars and hit-making album producer, died on Sunday in his New York City apartment. He was 75. A rep for the NYPD confirmed the singer’s death to Rolling Stone.

At approximately 3 p.m. ET, police officers responded to a 911 call at Ocasek’s home at 140 E. 19th Street, the rep said. Officers discovered Ocasek unconscious and unresponsive. He was later pronounced dead at the scene, though no cause of death has been revealed. A rep for the New York City Office of Chief Medical Examiner did not immediately reply to a request for comment.

Beginning with the Cars self-titled debut in 1978, Ocasek established himself as a stoic frontman with a sense of humor and melodrama on songs like “My Best Friend’s Girl,” “You’re All I’ve Got Tonight,” and “Good Times Roll.” As a member of the Cars, Ocasek helped kickstart the new-wave movement by pinning his disaffected vocals against herky-jerky rhythm guitar, dense keyboards and dancefloor-ready beats, and as one of the group’s lead vocalists, alongside bassist Benjamin Orr, he sang the hits “Shake It Up” and “You Might Think.” With the exception of only a couple of songs, Ocasek wrote every tune the Cars recorded. After the band broke up in 1988, Ocasek recorded as a solo artist and worked as a producer, helping sculpt blockbuster hits like Weezer’s blue and green albums and cult favorites like Bad Brains’ Rock for Light.

Ocasek was born to a Polish Catholic family in Baltimore. His father was a computer systems analyst, and he was sent to a parochial elementary school, where he was kicked out in the fifth grade. He told Rolling Stone in a 1979 profile that he couldn’t remember why he’d been expelled, though he said he aspired to be what he called a “drake,” a tough kid. He fell in love with the Crickets’ “That’ll Be the Day” when he was 10, prompting his grandmother to give him a guitar, though he didn’t take to it immediately. He became a rebel in his teen years, running away for weeks at a time to the beach town of Ocean City, Maryland.

Ocasek was born to a Polish Catholic family in Baltimore. His father was a computer systems analyst, and he was sent to a parochial elementary school, where he was kicked out in the fifth grade. He told Rolling Stone in a 1979 profile that he couldn’t remember why he’d been expelled, though he said he aspired to be what he called a “drake,” a tough kid. He fell in love with the Crickets’ “That’ll Be the Day” when he was 10, prompting his grandmother to give him a guitar, though he didn’t take to it immediately. He became a rebel in his teen years, running away for weeks at a time to the beach town of Ocean City, Maryland.

His family relocated to Cleveland when he was 16, and he decided to shape up and get good grades so he could attend a good college, but he ended up dropping out anyway and became interested again in guitar. This time it stuck, and he started writing tunes regularly. “After I started writing songs, I figured it would be good to start a band,” he told Rolling Stone. “Sometimes I’d put together a band just to hear my songs. If a person couldn’t play that well, there’d be fewer outside ideas to incorporate.” One of the musicians Ocasek drafted was Benjamin Orzechowski (later changing his last name to Orr); he helped record one of the demos.

Ocasek and Orr relocated to New York City, Woodstock and Ann Arbor, Michigan, singing Buddy Holly songs as a duo or playing hard rock so they could open for the MC5. Eventually, they settled in Cambridge, Massachusetts and formed a folk trio called Milkwood, releasing an album in 1972. They both struggled financially — Ocasek worked in clothing stores to keep his family fed — and eventually they met the musicians who would form the rest of the Cars and the group gelled in the winter of 1976. Ocasek wrote all the songs and acted as a benevolent dictator.

“The way it worked was, it would either be on a cassette, or Ric would pick up his guitar and perform the song for us,” Cars guitarist Elliott Easton told Rolling Stone. “We’d all watch his hands and listen to the lyrics and talk about it. We knew enough about music, so we just built the songs up. When there was a space for a hook or a line — or a sinker — we put it in.”

The Cars’ self-titled album, which Queen producer Roy Thomas Baker helmed and recorded in just two weeks, came out on June 6th, 1978 and became a Top 20 hit in the U.S. It was later certified sextuple platinum on the strength of the hits “Just What I Needed” (sung by Orr), “My Best Friend’s Girl,” and “Good Times Roll.” The record is also home to a couple of songs that became hits later, including “You’re All I’ve Got Tonight” and (with some thanks due to it soundtracking a pivotal scene in Fast Times at Ridgemont High), “Moving in Stereo.” “Ric was very, very sober and very down to earth, which is rare,” Baker told Rolling Stone.

They swiftly followed it up a year later with Candy-O, which contained the hits “Let’s Go” and “It’s All I Can Do.” By then, new wave had become a hot commodity and the LP made it up to Number Three and was subsequently certified quadruple platinum. The group had leveled up to being an arena band. The following year’s Panorama made it up to Number Five but was a bit of a dud; it went merely platinum and contained only one hit, “Touch and Go,” which barely made the Top 40. They corrected course with 1981’s Shake It Up, which they recorded in their own Intermedia Studio in Boston. It made it up to Number Nine but was certified double platinum. The album featured the hits “Since You’re Gone” and the anthemic title cut, a Number Four hit.

The band hit critical mass in 1984 with Heartbeat City, an album that issued five Top 40 singles in the U.S.: “You Might Think,” “Magic,” “Hello Again,” “Why Can’t I Have You,” and the monolithic “Drive,” which Orr sang. “Drive” also served as the background music for ads for African famine relief during Live Aid; when the song surged in popularity in the U.K., Ocasek donated his royalties to the Band Aid Trust. Their video for “You Might Think,” in which Ocasek became a voyeuristic fly, bested Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” at the MTV Video Music Awards that year and won the Moonman for Video of the Year. The record, which made it up to Number Three, is now quadruple platinum.

Read the rest of this article at Rolling Stone